Jonathan Richman | Dogmatics Photo | Paley Brother's Story

Boston Sound Home Page

The Boston Sound Revisted By Robert Somma

Fusion Magazine - December 1969

If Boston and MGM were dead and buried, this article would be nothing more than an autopsy of a disinterment. But I’ve no desire to play doctor or rob graves and I don’t groove on the odor of decay. Even more to the point, though the landscape is littered with bodies, there isn’t really a corpse. Boston and MG-M, with arms linked and usually in step, marched through a rock music campaign during the past two years and they both show the wounds. It seems to me that they’re sufficiently healed not to give much pain when you touch—still, they’re serious enough to leave scars.

If Boston and MGM were dead and buried, this article would be nothing more than an autopsy of a disinterment. But I’ve no desire to play doctor or rob graves and I don’t groove on the odor of decay. Even more to the point, though the landscape is littered with bodies, there isn’t really a corpse. Boston and MG-M, with arms linked and usually in step, marched through a rock music campaign during the past two years and they both show the wounds. It seems to me that they’re sufficiently healed not to give much pain when you touch—still, they’re serious enough to leave scars.

The losses in morale and money which Boston music and MGM record company incurred during 1968 are reasonably well-known within the record industry, to managers and promoters, to reviewers, publishers and producers, and even by those who have only a passing interest in marketing matters, the general public. Despite the complexity of detail and the extent of the damage to reputations and to purses, the major facts of the experience are simple and easy to digest. There were, clearly, miscalculations and misjudgments made in advertising and promotion departments and among bands. There is an understandable reluctance on the part of some of the people involved to discuss explicitly the moments of decision and commitment. I have no interest in relegating responsibility and only an indirect one in assessing it.

There is, to be sure, blame available, but if it helps to pin it on record company executives, group managers, and ad agencies,

I'm not completely convinced that it would be useful to do so. I am interested in the chronology of events and in the nature of the circumstances which made it possible for both Boston and MGM to suffer such large losses in capital, prestige and confidence in so short a period of time.

Numerous personalities play leading roles in the drama: managers, promotion representatives, agents, editors and writers, top-level executives, low-level hangers-on, producers and musicians. Anyone approaching the Boston Sound, its pre-promotion musicians and deejays and its post-promotion apologists need to have a flair for the coherent and the fair. Every side of the story has its explanation, its impulse, its logic. Opposed views on the matter are held and it's easy to see why they can coexist. Ray Riepen, who owns the Boston Tea Party, was actively invo1ved in the presentation of the Boston groups. His estimate of the experience?-"Tragic-it set back Boston music two years." Dick Summer, then WBZ's deejay, moved from Boston to New York in the wake of the deflation, then back to Boston to WMEX. He has different view: "The Boston groups reached a large audience. I'm a deejay and I'm supposed to help develop local talent, I'm not ashamed of having had anything to do with it." Summer, like Riepen in his hall, played an important role in presenting Boston groups on the air. The prime movers in the Boston Sound are still around, if not in precisely the same capacity: Riepen's interests have expanded; Summer is a program director; Alan Lorber continues to produce in New York; Ray Paret still operates Amphion in Boston; Harvey Cowan and Lennie Scheer work for MGM; Newsweek magazine, last time I look, still publishes.

In the end, it's a matter of evaluating the known facts and drawing a conclusion which those facts could support. I believe the report which follows is a fair and comprehensive accounts of my efforts at unraveling a real event in the record industry, not to

prove I could perform a resurrection, but with the conviction that my conclusions are evident and sound enough to warrant attention. The only advantage I have over the parties involved is my admission that, as in everything else, there is no one opinion or

interpretation which binds all the various participants. Perhaps not even mine.

To begin in the most general way, the groups which had most

to gain and most to lose during the winter of 1968 were Ultimate

Spinach, Orpheus, and the Beacon Street Union. At the other end of the see-saw sat M-G-M records, a company which, even in mid-67 had a reputation for density and inflexibility at the rate level. And midway between record company and rock groups were the notable and, it seems, essential middlemen-the managers and the producers.

Especially the producers. They had something the managers and the groups required before they could even begin to think in terms of commercial success, particularly recording success- contacts, experience, leverage within the industry based upon a demonstrated ability to achieve sales.

The group which made the largest gain in financial terms,

that is, in record sales, was Ultimate Spinach, and it is for this reason that theirs is perhaps the most bitter experience. It was certainly the most extreme. Before the summer of 1967 they were just another rat in the race toward recognition in the rock market, with no national identity, no recorded material, no definite direction and lots of competition. One year later, they were booked into major cities across the country, and had sold a million dollars worth of records. They had been praised and analyzed,

puffed up and put down in trade journals, national magazines, rock publications and the Wall Street Journal. They were mentioned in the same paragraph and on the same terms with the

the Rolling Stones, and the Jefferson Airplane (by Nat Hentoff, in Jazz and Pop). They were hailed, typically, in Time

Magazine as the "Jolly Green Giant of pop." It would be inaccurate to say that a completely undeserved success had been thrust

upon them-but it's damn sure they had reached first base without much panting

and without having hit the ball out of the infield.

One year after all that, and Ultimate Spinach no longer existes,

except on a few poorly moving LP's in the catalogue of a record company in trouble. No one will, or can, say whether it was in the stars or in them, but Ultimate Spinach and MGM like the scientists in the opinion of Oppenheimer, know guilt.

During the summer of 1967 the music scene in Boston was healthy, if not especially central to the rock movement

,whose focus had shifted dramatically to San Francisco. Out West, the

Monterey Pop Festival, the attention of national magazines, the allegiance arid optimism of a new generation, all contributed to an excitement and an intensity of activity in rock which would make 1968 the year of commercial ascendancy for the groups which had developed and grown there. Back East, New York had neglected or smothered its own groups, as New York seems to think necessary, thus surrendering whatever claim it might have had on the record industry as a fertile ground for new and active talent. The bands and the personalities were elsewhere, the direction was West and the distance was several thousand miles.

Cambridge (with its large concentration of students), was a huge market as well as a natural source of musicians, writers, agents, businessmen and fans. The folk movement had its heart there, if not its commercial mind, and the college community actively supported and contributed to the folk scene. The AM stations, WBZ in particular, weren't starving, though they simply had no Boston groups to promote. The entire city was geared for coffee houses, acoustic guitars, meaningful lyrics and a cerebral response to music. Attempts were made, not unsuccessful and at without reason, to attract rock groups, both at the Unicorn and at

the Boston Tea Party. In July of 1967, Boston was ripe for a homegrown product to emerge and prepared to give such a group

grass-roots support. But for that to happen, the city and the group had to rely on forces which stood outside of the city and

which, in some ways, had other interests at heart than Boston's best.

It is important to realize that in the summer of 1967 more than one independent producer or fledgling manager must have

made the manifest judgment that the East Coast could, if the right procedure were followed, duplicate the success of San Francisco. It was a commercial decision, and a sound one, based on a defensible estimate of market direction and available talent, for some producer or record company to tap the resources in the

Boston area. The groups were forming, making the largely imitative moves toward the market, And young, market-oriented

dudes in the record industry were well aware of the possibilities.

Alan Lorber was certainly interested in Boston as

a source of commercial talent and his interest coincided with the evolution

of group called, first, the Underground Cinema, then Ultimate Spinach.

This group was brought to Lorber's attention by Amphion the management

agency of Ray Paret and David Jenks. Paret signed a contract

with Lorber, who, as an independent producer had made a reputation and

sales of $32 million and who had established a working relationship with MGM.

Lorber had carefully formulated his approach to the new market by releasing to the trade journals, on September 23, 1967, 'plans for the development of the Boston scene. His reading of the market was, on a certain commercial level, a fair enough estimate of the then-current trends and tastes. At any rate, there seems, in retrospect, to have been a definite stir in the commercial waters:

Lorber feels that Boston will be more successful as a talent center than San Francisco has been. He feels that there was only a moderate talent situation in San Francisco which was backed and forced by strong commercial interests.

(Record World-Sept. 23, 1967)

It is pertinent to note here that Lorber attributes at least part of ultimate failure of his enterprise in Boston to a reluctance on the part of local interests to support their own groups.

It is pertinent to note here that Lorber attributes at least part of ultimate failure of his enterprise in Boston to a reluctance on the part of local interests to support their own groups.

Lorber's procedure with "fresh talent" involved signing a group to his production company, producing tapes which would be sold under contractual agreement to M-G-M for promotion and distribution. This type of arrangement is known in the industry and can serve the interests of all parties, depending, of course, upon the specific terms of the agreement. M-G-M was committed to function in areas for which, presumably, it was well qualified, i.e., selling records. Lorber knew, from his singles experience, the ropes of production. In effect, the music of the group and the group itself were in the hands of a combination of interests, primarily Lorber, who would pass the product on to M-G-M. The implication in this is not that there is something unprofessional or unfair in the operation of either the record company or the producer, but, rather, that the commercial destiny of the group passed, under such an agreement, out of its control. In many cases, this is a fortunate thing. For Ultimate Spinach, the happiness was short-lived. By October of 1967 Lorber had completed taping with Ultimate Spinach and a release date was scheduled for the end of the year. In the interim Orpheus (a still operative band) had signed a similar contract with Lorber, while Wes Farrell had found the Beacon Street Union. The commercial interests, which had at first just sniffed around, were now well into the hunt.

Here it's perhaps important to give some idea of the executive state of affairs at MGM. The record division of the parent company was in the hands of older men, individuals who, over the years, had committed the label to certain artists and groups. These last were a costly investment for the company. M-GM channeled large sums of money into producing, advertising and promoting artists whose market value had crested by the mid-sixties. The Boston Sound promised a financial return which could help offset the losses which had become almost institutional within the label. Hence MGM approached the comming scene with enthusiasm. A decision was made, at a high corporate level to commit the label to an advertising and promotional push. It appears, again after the fact, that it was, shall we say, indelicate and imprudent to place the groups under a single logo. Lorber even now contends for his own reasons, that it

was a natural thing to do, given the type of competitive marketing within the industry and the image-lusting mind of the audience.

In this, Lorber finds support in the opinion of Dick Summer, who states with emphasis that "the promotion was a good idea, it was natural to try to reach the largest possible audience at that level." At best, the Boston Sound set up the groups and the label for a put-down. Thus, while it is undeniable that the producers of the Boston albums had an ear for the commercial sound, other factors came to dominate, factors not unprecedented though obviously unforeseen.

The first Ultimate Spinach album was to be released in December of 1967. But the release was delayed. M-G-M was preparing a promotion campaign for all three of its groups, which included trade ads for "the sound heard round the world-the best of the Boston Sound." Even prior to the Boss-town piece in Newsweek, MGM had planned a series of "press parties" for the three groups. Ultimate Spinach had several in its honor, in New York, on the West Coast, and at points in between. Beacon Street Union and Orpheus participated in similar ventures at the Scene and the Bitter End in New York. Ultimate Spinach was booked for a mid-January tour of the West Coast, and MGM continued to hold off on the LP release. After a farewell at the Boston Tea Party, the group went West, where they were met with an at first receptive audience. During the tour an event occurred which assured that the audience would turn against them and which must be viewed as one of the major steps in a long line of fateful, perhaps well-intentioned but finally unfortunate, if not disastrous communications movements.

During the last week in January the groups and the city stood poised on the verge of a rapid trip up and down the ladder of commercial success. Hopefully, the Boston groups would inject vitality into a pallid rock label, enhance an East Coast music scene and stimulate a lively cash flow toward the principal

figures. On January 28, 1968, Newsweek magazine published its piece on the "Boss-town Sound." Lorber states that neither he nor M-G-M was approached by the researchers or reporters from the magazine. I'm not convinced either of them would have balked at the tone and substance of the article, which was, in effect, a lame piece of unsolicited ad copy. It was also a loaded piece of reporting, laced with quotes from club owners,. managers, and musicians. The statements sounded synthetic and the coclusions were generally useless:

from one Radcliffe girl:

They’re Thomas Wolfe in sound, with words that make you gloomy but always gladder.

and:

However diverse, the Boston groups are held together by their general folk orientation, their subdued, artful electronic sound, an insistence on clear, understandable lyrics, the spice of dissonance and the infusion of classical textures.

The point, of course, isn’t that the Newsweek report was a piece of artless trash, but that it seemed to have originated with the producer and the record company and the groups.” The misapprehensions and absurd precious-pop style weren’t so indigestible as they were suspiciously similar to the worst promotional ploys in the business.

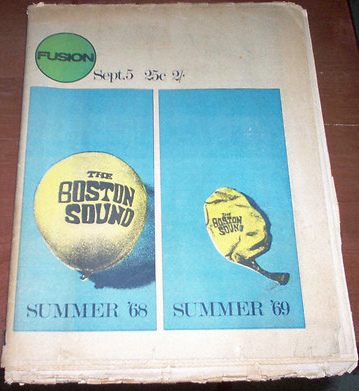

The response to the combination of national phrase-making in Newsweek and the intense promotional activity of MGM was complicated at the time, but predictable. The Boston groups found themselves the recipients of heavy record sales (75,000 in three weeks for Ultimate Spinach) and bookings, along with the testy and defensive disdain of the younger critics who knew a dog when it barked. The net result of the press exposure both in the form of articles and reviews as well as ads, was similar to a balloon, filled with air, untied and let loose from the hand of a child—an upward thrust and a long fall to earth.

The exposure was quite massive and comprehensive. After Newsweek had keyed the audience-sensitive media to the topic,

the press converged and like a huge vacuum cleaner sucked Boston Sound into its machinery, ingested it into its belly, there to be roughage for an acidulous process whose known end is part nourishment and part waste matter. From February to July of 1968, everyone who wrote on any subject even remotely concerned with popular culture did his or her thing on either the Boston Sound or one of its representative groups. Feedback was inevitable. It wasn’t just Newsweek, but Vogue, the Village Voice, Time, Rolling Stone, Jazz and Pop—you consciously marched back and forth across the spectrum of clout in American publishing if you simply set down the whistle-stops where Boston Sound made its printed appearances.

Three articles are vitally important, especially if one takes the most reasonable view of the incipient move toward the audience being made by the Boston talent, viz., that it didn’t seem likely for any one of the groups to have reached a stage of development, whether as performers or as recording artists, which could justify the attention or overcome the hype.

The Newsweek piece, ill-advised, insidious, perhaps not even

well-intentioned, put the groups right up there, grabbed the market by the earlobe and said “listen.” The effect of this was, at best, negative—it reduced the stature, the promise, the qualities of the Boston talent to a conglomerate “sound” your parents would belch over, in between coffee, Time, and the TV. But the

real audience, the one with the cash and an ear for the music, the one which responded to every flicker on the communications board, was hyped to the groups and came to them in an unnatural, forced manner and at an inopportune time. They were put on to them by one of the publications irrevocably identified with a different generation, and for all that under-twenty-fivers read Newsweek, they don’t quite believe everything they find there. They took the groups home on record to see whether it was the real thing.

From that point on, nothing particularly unanticipated happened. The guarantee of initially large sales was in, and the sales sheets would come after the audience had radically changed its direction. A kid who bought The Eyes of the Beacon Street Union in March would be an entry on a summer account-sheet, but, by then, would have turned his thumb down. The prosperity, in other words, was false. And if the audience was (and is) a demanding one, even as to how it wishes to be manipulated and exploited, its critics were in a position to put those demands in an articulate no-bullshit way. Two articles reflect the division in market between the establishment reading of a trend and the more accurate and up-to-date rejection of it-one in the Wall Street Journal and one in Rolling Stone.

.

Jon Landau, by early 1968, had already begun to establish himself as a sort of dean of rock critics. Even he was unaware, at that point, of the immense influence he possessed as resident arbiter of Rolling Stone. Landau had written direct, generally excellent pieces in Crawdaddy, knew about rock as a musician and as a critic, and had been around the Boston scene as long as there had been one. He seemed the perfect writer to review and evaluate the Boston Sound, the most appropriate index of its validity and its worth. Coincidental with Landau’s emerging status was the rise of Rolling Stone and the equally emergent d resentment of the West Coast and of the San Francisco area for the East. Cultural chauvinism is nothing new, but as Rolling Stone overtook the audience which had become dissatisfied with or alienated from Crawdaddy (whose offices at the time were right on 6th Avenue off West 4th Street and, later on, on Canal Street-nothing more East than New York) the West Coast began to resent the implication that San Francisco was, at the beginning of 1968, musically barren or that Boston had taken up the baton and was circling the track, heading the field and about to take over commercial supremacy from the West.

Landau’s piece on the Boston Sound was a nail in the coffin, if we can agree that the Newsweek article, for all its obvious publicity value, had already put on the lid. He expressed every fear and suspicion the rock audience had for the Boston-based groups, most especially as they had been presented in Newsweek:

The side of Boston that is reaching the national audience with the first three of the albums is inextricably bound to an extremely heavy promotion by M-G-M and the question should really be whether or not there is anything lying beneath the hype.

Landau confirmed, both implicitly in his tone and explicitly in his evaluations ("pretentious," "derivative," "extremely pretentious, angry and self-righteous," "boring") most of the suspicions, almost by rote and in a deliberate and balanced way. He saw merit in certain of the groups or in certain aspects of a single group, and his evaluations were accurate in terms of what the groups had produced and released. But from a commercial point of view, it was a real down. He did mingle his own tastes and inclinations with his judgment of the Boston Sound, but for all that one could dispute the peripheral details of the Boston scene or blame him for neglecting to calculate the long-range effect of his article, he was right. The Boston Sound was a creation of a publication and of a promotion department and as such was neither justified by the records of the groups nor particularly sought by the groups themselves. Implicit in its growth was the death of the bands and when, later on, money and the audience had dried up, the arguments would center on one or another individual or event as blameworthy.

Still, for all that the game was decidedly over, there were plenty of moves and many months left. Exposure in large-circulation publications and the consequent one-shot record sales brought intense market activity for the groups, as performers and recording band. Bookings were set up and the groups hoped that the sales fervor would carry over from their first to their second lp.

For Ultimate Spinach, the testimony of this activity came in May of 1968, not even a year after they had made their initial contract with Lorber. The Wall Street Journal, locus for prudent, topical and well-written articles on matters interesting to anyone even remotely identffiable as a consumer, carried a front-page essay by a staff reporter on the topic Selling a New Sound. If ever an autopsy was performed on a live one, this was it. No aspect of the group’s success was overlooked, not even the fragility of the entire trip:

The Ultimate Spinach, four boys and a girl, is one of hundreds of

Professional rock groups trying to make it. Most won’t. Bad music will wreck some. Bad management will finish others. High living will be the downfall of some.

Background information on rock, on its commercial realities, its internal organization, its market sensitivity was cited. The Ultimate Spinach was analyzed primarily in terms of a group moving against this background. Much of the detail put down in the article wasn’t all that new and gave off an odor of the half-bakrd ("It is music for collegians and drop-outs and others of the Now Generation, those in the know explain"). Its quotes, like those in Newsweek, seemed selected more for their entertainment value than for their fidelity to reality-at least, one hopes that to have been the case:

Mort Nasatir, then head of MGM’s record division:

Some of this music is so intellectual that it is a little like the poet

T. S. Eliot with his seven layers of ambiguity in each line.

Ian Bruce-Douglas, Ultimate Spinach leader:

We try in our music to get across the idea one should be free and

not bound by anything.

Rick Sklar, program director at WABC:

Often this kind of music runs on and on . . . It’s designed to simulate an LSD trip.

On the whole, the Wall Street Journal article was an exceptional piece of reporting, given the context and location of its appearance. It certainly indicated, however long after the fact, the impact of rock on the commercial apparatus. It even suggested, however faint-heartedly, something which, out on the street, was a known fact: Ultimate Spinach had not quite made it.

One of the peripheral phenomena of the trip to this point was the active proliferation of Boston groups and their signings with major record companies: Eden’s Children (ABC) and Earth Opera (Elecktra) were the most attractively packaged. If anyone, either within the groups or within the record companies, suspected that a comedown (or better, a bring-down) was in order, no one actually let on. Articles in the trades as late as July of 1968 continued to extol the success of the Boston Sound. The reverberations of Landau's "no", which only echoed as much as it keyed the audience, didn’t seem to have quite penetrated the conpanies.

At this point specific problems began to exert internal pressure. Ultimate Spinach, in particular, experienced, in the midst of its commercial success and press attention, personal difficulties native to the rock business. It seems clear enough now, even to the individuals directly involved, that Ultimate Spinach could not cut its bookings. They simply could not play up to the hype or the expectations of the press and the audience. That failure, coupled with the undercurrent negative response, killed off the band. Lorber, with some reason, points out that the band found itself in a position which demanded a personal and a professional maturity which were not quite there. And while some bands are given enough time to work out the various problems of their profession and their own lives and ambitions, the instant and overexposure denied such time to Ultimate Spinach. They were brought along much too fast and could not perform the difficult self-braking required by the commercial pressures, all of which pushed them more and more quickly.

It was only natural, considering the presentation of Boston talent in press and in promotion, that failure at the top would drag down the other bands and cause the "scene" to collapse. In some ways, it had been a gamble similar to our national politics -whether wisely or not, various groups were tied to a party line

and when the head of the ticket could no longer command enough votes, the public rejection, fair or not, was comprehensive and across the board. The groups were locked in-they could no more dissociate themselves from the logo than they could persuade the large national audience of their individual identities.

The pressures over which they had no control and which had

tried to operate in their interests only turned on them in the end. The groups continued to record and to perform, of course, but as a long-term commercial venture, the Boston Sound had been rejected. When it was proved that a backlash works in music as it does in politics, the success and the demand withered, and with

that the enthusiasm and optimism for a Boston scene.

At M-G-M the experience looked, from the outside, like an unmitigated disaster. It’s most fair, though, to point out that M-G-M records did not lose the 3 or 4 million dollars it’s said to have lost in 1968 because of the Boston groups, and it certainly didn’t lose that much on them. A source close to the operation estimates, with some authority, that MGM lost in the vicinity of $100,000 on the Boston Sound, MGM’s record division troubles predated 1968 and have already been suggested in this article.

In any case M-G-M did lose money in its record division and even more through its parent company’s movie interests. The executive decisions which aided and abetted the Boston Sound only reflected, particularly in the eyes of the public and the parent company, the susceptibility to miscalculation on the executive level of the record division. The Boston Sound was simply the most aggravated and latest case in point. For this reason M-G-M suffered through a period of great tension and even greater ambiguity and lack of direction during 1968 and 1969. With the departure of Mort Nasatir as president of the record division, there was a void filled, temporarily, by, first, Arnold Maxim, and then Sol Lesser, neither of whom was expected to act as more than interim appointee. Early this year, when matters were particularly acute and before any real commitment to a tangible change in attitude and approach was evident, a source at M-G-M described the effect of the Boston Sound on the executive level with this comment: “They’re all sitting around, waiting for the axe to fall—would you feel much like talking about it?”

These circumstances didn’t breed confidence or goodwill not to mention job security or public trust. Thus, even if Boston didn’t cost M-G-M much money as a direct investment, it did help to exaggerate or pinpoint already existing difficulties within the record company. It’s too easy to hang the rap on Lorber for pushing a scene and a group to commercial success prematurely or on MGM for lusting after a piece of the market; or on writers and editors for hyping a sound in a thoughtless way.

Certainly the Boston experience didn’t help MGM solve its problems but it did occasion a large-scale assessment of company policies and practices and understandably led to realignments and replacements in personnel. More than anything else, though, it implicated the record company in an unsuccessful promotional ploy and it did not help to inspire respect among new talents or to make the label attractive to the market. Still, good did come out of it. With a new president, a more tactful advertising head and a sea of commercial hazards carefully charted, the label is at least prepared to market the groups it still has and the ones it can attract in a more credible way.

As a scene, Boston may or may not exist, although I doubt it ever could in the simplistic way understood by national publications and promo men. All the assumptions made by the press and the producers are true enough—there are clubs, there’s talent, there are interested commercial heads. Dick Summer, for one, remains convinced that Boston is fertile ground for new groups, given the proper handling: “Now we’ve still got a huge untapped source of talent in Boston and I’d like to attempt to put it back into the spotlight.” But whether Boston could ever support a scene, either in the clubs or on the air, depends upon your definition of the term and, in any case, is a moot point at the moment.

The effect of the experience with the commercial realities of producing and marketing on the three bands most involved is mixed: Ultimate Spinach, to put it briefly, blew it, and even if it had plenty of encouragement to do so, the group must surely regret, with the sense of an opportunity lost, the circumstances and the failures of the past twenty months. Beacon Street Union has settled back into local band status, playing high-school gyms, Probably discouraged enough to sense the unlikelihood of recovering the original impetus. Orpheus has survived, seems to have matured, and continues to play and to record. In the end, for whatever it’s worth, they responded best to the restraint and guidance Lorber seems interested in providing.

Plainly, there are lessons here, for the audience as well as its closely watching media-men. And if the individuals involved don't need to be reminded, others could with profit make their own observations. MGM tied itself to a process of promotion which was inappropriate and untimely. The groups were placed before the public and on the market prematurely, before they were personally and professionally ready to deliver. The bands didn’t demonstrate an understanding of the demands and consequences of success. It’s not impossible to put a group in front of the public, but management and marketers should place more faith in the rule of thumb that at some point in the evening, when the glasses are empty and the lights are out, and all that remains is you and the lady you’ve been courting, you’ve got to come across.

Home | WLYN | WMBR | Boston Groupie News | Punk Photos | MP3's | Links

Jonathan Richman | Dogmatics Photo | Paley Brother's Story